Home / Destinations / Historical / Ruins /

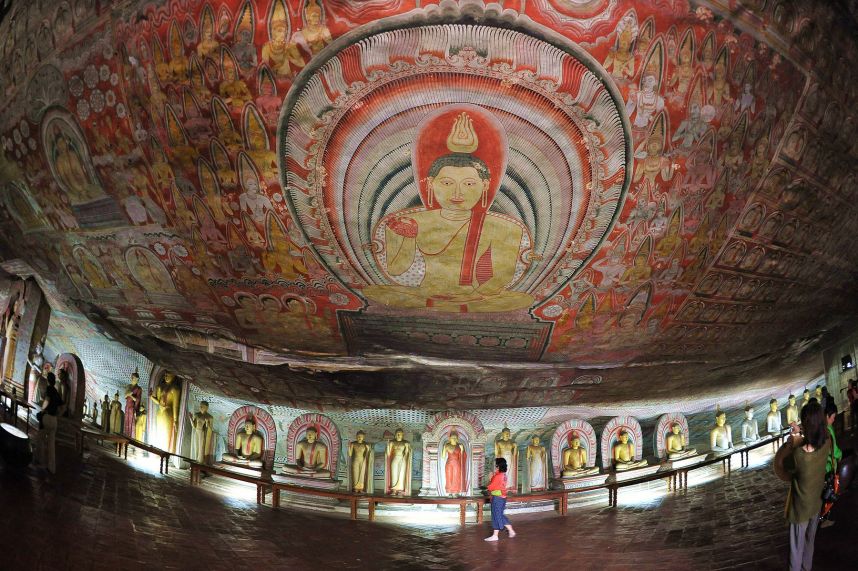

Dambulla Cave Temple

Last updated on 26 Jun 2023Show location

Like the Mihintale caves, the caverns of Dambulla were first inhabited by hermit Buddhists. The discovery of pre-Christian inscriptions in Brahmi characters immediately below the drip-ledge of the central cave serves as proof of the location's age. "Damarakita teraha lene agata anagata catu disa sagas dine," reads one of these inscriptions. Abaya rajiyahi karite Gamani Given to the Community of the Four Quarters, present or future, is the Elder Dlmamma-cave. rakkita's during Gamani Adhaya's rule.) All of the short Brahmi inscriptions at Dambulla have characteristic letter shapes that date to the first century B. C., when Abhaya, also known as Vattagamani Abhaya, was the only ruler (89-77B. C.). This proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that the king Abhaya referred to in the inscription previously cited is Vattagamani Abhaya. At the very least during the reign of this king, Dambulla gained popularity as a destination for Buddhist monks. One of the few monarchs of ancient Sri Lanka whose reputation is independent of recorded accounts is Vattagamani Abhaya. The majority of the country's residents give him credit for tiling the countless drip-ledged caverns that once housed Buddhist monks. As we've seen, a few of these caves, including Dambulla, really have inscriptions that bear the royal name that is attributed to him.

Tradition has it that monks living in caverns like Dambulla helped Vattagamani Abhaya flee his kingdom of Anuradhapura when it was besieged by people from the south of India. During the reign of this king, Buddhist monks at Aluvihara are credited with putting the Buddhist scriptures on paper for the first time, according to the Mahavamsa. This can be viewed as strong proof that large caves like Dambulla and Aluvihare in the island's center served as Buddhist monks' residences during this early time and were also supported by the monarchs of Anuradhapura. Tradition also holds that during the reign of Vattagamani Abhaya, the five seated Buddha statues, including the main one in Cave No. 4 of the Dambulla temple, were carved out of natural rock. Moreover, some of the images in Cave No. 2 and the main images in Cave No. 1 are thought to have been created during the rule of this king. No credibility can be given to this tradition because there are no Buddha images in Sri Lanka that date back to the first century A.C. This does not, however, rule out the likelihood that at least some of the images in these cases were created during and after the eighth century A.C., which is the later Anuradhapura period. Regrettably, due to the repairs and modifications carried out in successive eras, these cannot be recognized. Following in his uncle's footsteps, Mahaculi Maha Tissa, Vattagamani's successor, devoted a large portion of his time to religious pursuits. One brief Inscription from Dambulla mentions a monarch by the name of Gemini Tissa, who could have been Mahaculi Maha Tissa. The following king to support Dambulla was Nissankamalla, who made frequent trips around the nation and was frequently referenced in his various inscriptions. As a foreigner, the monarch undoubtedly intended to make his presence known throughout the island and also hoped to gain the people's support by giving out alms during these outings. The king appears to have had a desire to travel to famous locations like Dambulla. During these trips, he visited Kelaniya and Anuradhapura and left a lithic record there. The chronicle states that Nissankamalla's fourth and likely final voyage took him to Dambulla, where he lavishly built a cave temple and installed 73 gilded statues of the Buddha. This king left a description of himself and his religious deeds in an inscription he carved into the rock between No. I and the gateway. The last two paragraphs of the record mention that he performed a large puja at a cost of seven lacs of rupees and gave the cave the name suvarnagiri-guha, which means "the golden rock cave," to the sculptures of the Buddha that were lying, sitting, and standing there. It is obvious that Dambulla (Jambukola-Vihara) became known as Suvarnagiriguha or Rangiri Dambulla after this point. While continuing to be a well-known religious center, Dambulla does not appear to have drawn the attention of Sinhalese rulers until the seventeenth century, when they entered the country's political scene following the fall of the Polonnaruva state at the end of the twelfth century A. D. The progressive collapse and depopulation of the northern and southeastern areas of the Island, as well as the shifting of population centers and kingdoms, were the most significant factors that had a significant impact on every element of Sri Lanka's history during this time. As a result, historic holy sites like Dambulla faded into obscurity.

In the XVIII century, Dambulla once more gained notoriety as a major religious hub. King Senaratna (Senarat) of Kandy (1604–1635 A.C.), according to the Dambulu Vihara Tudaputa (a palm-left manuscript) of A.D. 1726, rebuilt and refurbished the temple. "After the conclusion of the renovations, which took three years, the king, on the festival of a painting of the eyes of the Buddha figures, proceeded to the temple with the three queens and the three princes," the record continues. The king requested the assembled monks at Maharaja Viharaya (cave No. 2) to nominate someone suitable to be appointed incumbent of this temple, of which 65 images, including the one in residing posture, had been painted and completed, as soon as the festival had concluded. The king stood on the semicircular stepstone of this cave. It's a good idea to have a backup plan in case the backup. Under the instruction of this king, Cave No. 3, which was formerly utilized as a storage, was further excavated and transformed into another temple roost. A well-done statue of this monarch wearing state clothes that closely resemble those used by the Kandyan rulers of the Nayakkar dynasty is located to the right of the cave's entrance.